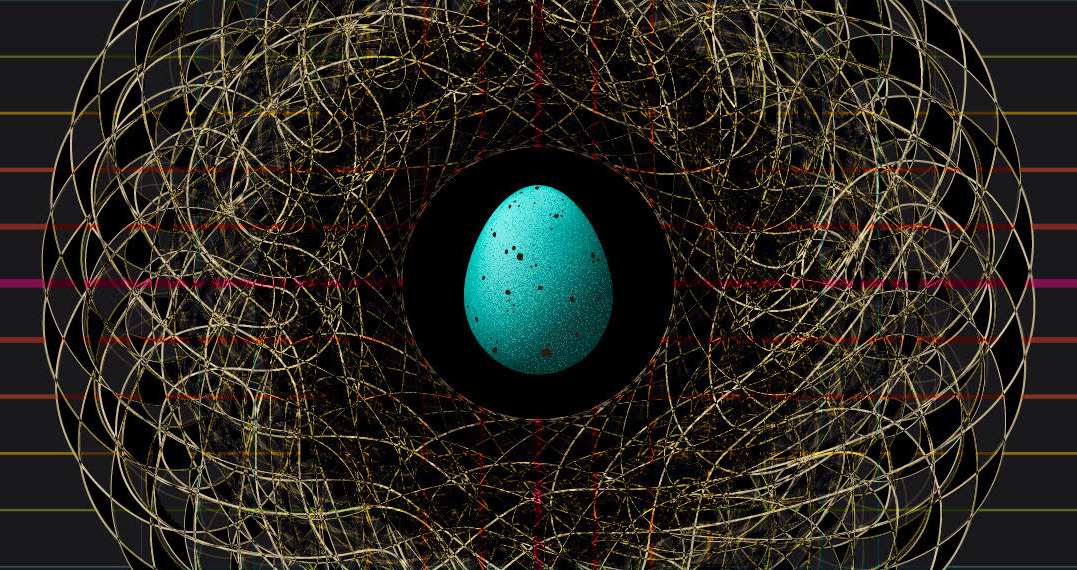

Allowing ideas to rest allows them to grow – and the space between enables some of the best thinking to appear.

‘Creative work’, a composer once informed me, ‘is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration’.

Snappy equation, huh? So I thought, and quoted it often. But, after a few years of devising creative, I began to realise it was lacking a critical element: incubation. That is to say, letting go of an idea and allowing it to yield more.

Incubation defies a constant time value – it can be minutes, hours, years or anything in between. For me it started with what you might term ‘speed-incubation’ (now there’s an oxymoron) when, as a young copywriter I was encouraged to apply an ‘overnight test’ to a written piece, to help evaluate it. It works like this: before you leave your desk for the night, pin up your ad, article or headline on the wall in front of the door so that upon arrival the following morning it will be the first thing you see and read.

Since any amount of time and distance is a physic for a malnourished idea and a purgative for a mediocre one, one look at that copy in the cold light of day would inform where on the scale of quality it fell, (10 being Shakespeare and 01 being sheepshit). Did the piece have enough inherent worth to be honed and refined, or should it be shredded without delay?

Much more importantly, what other ideas had presented themselves, uninvited, in that intervening space? Had the concept morphed at all as the brain had worked on it in the shadows? I was surprised at how often it had.

Store your ideas in the cellar

il21 / Shutterstock.comThe German composer, Richard Strauss opined on this. ‘Ideas, like young wine,’ he said, ‘should be put in storage and taken up again only after they have been allowed to ferment and to ripen.’ Perhaps medium-term incubation could be thought of as ‘rumination’, passively allowing your mind time to work on the problem while you focus on something entirely different, occasionally bringing it back up for consideration. Again, during the timelag, alternatives may well materialise.

il21 / Shutterstock.comThe German composer, Richard Strauss opined on this. ‘Ideas, like young wine,’ he said, ‘should be put in storage and taken up again only after they have been allowed to ferment and to ripen.’ Perhaps medium-term incubation could be thought of as ‘rumination’, passively allowing your mind time to work on the problem while you focus on something entirely different, occasionally bringing it back up for consideration. Again, during the timelag, alternatives may well materialise.

The process can also be very long-term. Steve Jobs’ account of visiting a student calligraphy class might be referred to as unintentional, long-term incubation. ‘When we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me,’ he said. ‘And we designed it all into the Mac. If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts.’

Pause on your journey

James Webb Young worked his way up from lowly copywriter at the US agency Walter Thompson, to Vice President of the huge company in the early 1960s. He was a believer in the power of incubation, and made it the central element in his five-part process for generating concepts.

‘This is the way ideas come,’ he wrote, ‘after you have stopped straining for them, and have passed through a period of rest and relaxation from the search.’1 He knew that ideas grow organically if you let them, with new permutations occurring and new connections being made.

‘This is the way ideas come,’ he wrote, ‘after you have stopped straining for them, and have passed through a period of rest and relaxation from the search.’1 He knew that ideas grow organically if you let them, with new permutations occurring and new connections being made.

Since few deadlines allow time for incubation, you need to be proactive in building it into your working practice from the ground up. To stop straining is a big ask. But as you do, you will allow your mind space to settle back and find alternatives – no sweat.

References

Top: Illustration: Marco Cazzulini

used with permission

1 Young, James Webb, A Technique for Producing Ideas (1965)